“In all fairness, I may like to sing, but if I don’t have the God-given talent then it doesn’t matter how much passion I have,” he said. “The problem with art is most people love to draw and they will find plenty of people to tell them they are good. The litmus test, however, is when people start paying you for your work.”

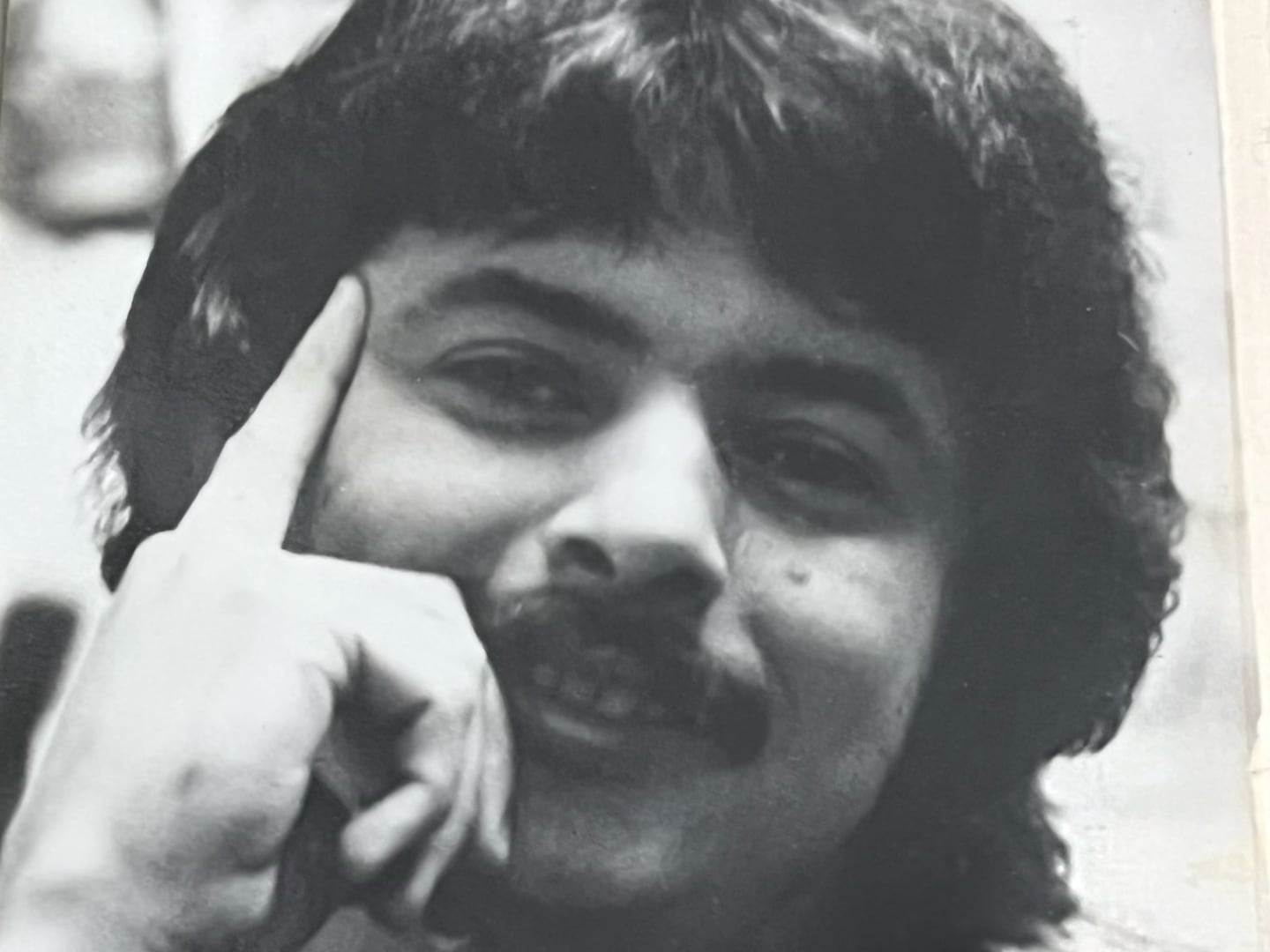

Rev. Johnson, who joined the Globe as an advertising department messenger in 1968 and said he persevered through 379 rejections before the newspaper finally published one of his illustrations, died in his sleep on Nov. 15. He was 75, lived in Canton, and formerly was a longtime Stoughton resident.

For about 25 years he cohosted the “Mustard and Johnson” talk show on WEEI with Craig Mustard.

“Larry brought humor, he brought wit, but he also brought a sense of spirituality,” Mustard said of their show, which ended a few years ago.

“He brought a different dimension — it was looking at things from 30,000 feet,” Mustard said. “It was an insight into human nature that I don’t think I necessarily had before working with him.”

Rev. Johnson liked to say he persuaded the Globe to create a sports cartoonist job for him when he was 19 and studying at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

He stayed at the Globe for about 20 years and left to join The National Sports Daily as a cartoonist. From there he moved to ESPN.com, where he drew cartoons for The Daily Quickie, and then to WEEI, where he contributed cartoons to the website along with his on-air duties.

Cartoons inspired by sports news and the exploits of famous athletes inevitably expressed opinions, which presented challenges.

“One of the reasons I don’t like meeting athletes is because it’s easy for me to like people, thereby making it difficult to poke fun at them when I have to … and I have to all of the time,” he wrote on his LinkedIn page.

Much of his sports cartooning took place during the decades the Red Sox went without winning a World Series championship.

The cover of his 2002 book “Honey, I’m Home! A cartoon tribute for suffering Red Sox fans,” shows a man in a Red Sox uniform, arms open wide with enthusiasm, leaping into an open grave with a tombstone that reads: “The Boston Red Sox 1919-2002.”

“They say that comedy and tragedy are so closely related that if the idea is delivered well enough, your audience laughs instead of cries, and cries when laughing doesn’t get the job done,” Rev. Johnson wrote on LinkedIn.

“The secret, of course, is to perform root canals in such a way that your fans are grateful that the pain is gone, and forgetful that they ever had the fear of having the procedure done in the first place. That’s cartooning!”

Larry Curtis Johnson was born in Boston on Oct. 12, 1949, and grew up in Canton, graduating in 1967 from Canton High School.

His mother, Jacqueline Williams Lovett, won awards for her innovative approaches to running business offices, Rev. Johnson’s family said.

He told Paccia that his father, Leonard Charles Johnson I, “was a famous musician who was the lead trumpet player for Quincy Jones, Duke Ellington, and Count Basie.”

His parents divorced and his mother married Roland Lovett. Rev. Johnson was close to his stepfather, who now lives in Prince George’s County, Md., and to Roland’s sons from a previous marriage, Darryl of Prince George’s County and Larry of Boston.

Rev. Johnson, whose first marriage ended in divorce, married Sharon Chandler, a teacher, in 1980.

They ran a business, Johnson Editions, and sold his fine arts paintings and prints to collectors such as Vernon Jordan and Oprah Winfrey, his family said.

“His luminous watercolors are animated by a genuine feeling for people, whether they’re professional boxers or straw-hatted ladies carrying baskets of flowers,” Globe art critic Christine Temin wrote in 1988 of Rev. Johnson’s work, which was on display in the Boston gallery of the Museum of the National Center for Afro-American Artists.

In his early 30s, Rev. Johnson added minister to his multifaceted career.

“My dad lost his grandfather, his father, and his brother by the time he was 30 years old, and so he was immediately ushered into being the patriarch of the family, which was a different thing because he was the youngest,” said his daughter, Nicole Johnson Townes of Chesapeake, Va. “Losing all the men in his family transformed his life, and he rose to the occasion.”

Rev. Johnson “gave people comfort. He was a great comforter,” his daughter said.

“My father was a natural encourager,” she added. “He woke up every single day with a zeal, a passion for life. He just had an energy about him that could literally transform a room.”

As a Black editorial sports cartoonist during Boston’s school desegregation era, and a person of color entering Greater Boston’s talk radio landscape when it was populated mostly by white men, Rev. Johnson “had the uncanny ability to cross cultural lines through his humor, his openness, and by meeting people where they are,” his daughter said.

His presence “caused people to change their perspectives about race and stereotyping,” she said. “I’m convinced that because of the way he treated people, he was able to change their outlook on the world.”

In addition to his wife, daughter, stepfather, and stepbrothers, Rev. Johnson leaves his son, Larry C.B. Johnson of Randolph; a sister, Lorraine Johnson-Graham of North Carolina; five grandchildren; and three great-grandchildren.

A funeral service will be held at 10:30 a.m. Monday in Farley Funeral Home in Stoughton. Burial will follow in Knollwood Memorial Park in Canton.

On “Mustard and Johnson,” the hosts disagreed most of the time about sports topics, Mustard said, which led some listeners to wonder if they disliked each other. The opposite was true.

“If you didn’t like a person off the air, you couldn’t argue like that on the air,” he said. “We were complementary characters.”

Mustard added that their quarter-century together “was the best experience I’ve ever had in radio, no question about it.”

Rev. Johnson, he said, “was such a compassionate empathic person, and I think he taught me in a lot of ways to be more compassionate and empathetic. The most honest I was, and the closest I was to who I am, was when I worked with Larry.”

Bryan Marquard can be reached at bryan.marquard@globe.com.